Sometime between 2002 and 2022, a guestbook documenting the visits of prominent musicians, composers, diplomats and others to the Berlin home of classical music impresarios Hermann and Louise Wolff in the early 20th century was stolen from the archives of the Berliner Philharmoniker, also known as the Berlin Philharmonic Orchestra.

Hermann Wolff, born in 1865 in Cologne, grew up in Berlin. Although he followed his father into business and was a trader on the Berlin Stock Exchange, his true passion was music. While working on the stock exchange, he began to also work for a music publishing firm and eventually set up a concert management agency in Berlin in 1880. Prior to starting his agency, he married Louisa Schwarz, an Austrian-born actress. Together, they had two daughters, Edith and Lili, and a son, Werner.

Between 1882 and 1887, Wolff helped to reorganize a failing Berlin orchestra, leading eventually to the creation of the Berliner Philharmoniker. Wolff organized the Berlin Philharmonic’s tours under its first conductor, Arthur Nikisch, to Russia, Spain, Portugal, Belgium, Switzerland and France. In 1896, Emperor Wilhelm II appointed Wolff to head the delegation of German musicians who attended the coronation festivities in Moscow for Nicholas II, the new Tsar of Russia.

Wolff was also behind the building of a new concert venue in Berlin, the Bechstein-Saal (Bechstein Hall), designed for chamber music concerts and solo recitals. That venue opened in October 1882, with a series of concerts in which well-known musicians, including Hans von Bülow, Joseph Joachim, Johannes Brahms, and Anton Rubinstein, performed.

Many renowned composers and musicians visited Hermann and Louise Wolff’s house in Berlin in the early years of the 20th century, especially in conjunction with “Philharmonic dinners” given there on Sunday afternoons after rehearsals with the Philharmonic Orchestra. The guestbook documented these visits to the Wolffs’ home.

Hermann Wolff died on 3 February 1902 at the age of 56. After his death, Louise took charge of the concert agency and continued the close collaboration with the Berlin Philharmonic, and continued the tradition of the guestbook. By the end of 1934, however, Louise dissolved the agency, recognizing that her daughters Edith and Lili would not be able to continue this work, given their Jewish ancestry. Louisa died in 1935 and, in 1942, Edith was interned in the Theresienstadt concentration camp. Miraculously, Edith survived that internment. The guestbook of Hermann and Louisa also survived and was passed by Edith on to the next generations of the Wolff family.

This remarkable piece of classical music history compiled by Hermann and Louise Wolff was given to the Berlin Philharmonic by their two great-granddaughters in 2002. It was discovered missing from the Berlin Philharmonic’s archives in October 2022 when one of the great-granddaughters visited Berlin, went to the concert hall to show the guestbook to her children and it could not be found. No information about the missing guestbook has ever been provided by the Berlin Philharmonic to this date.

A Little History About Where the Theft Happened

The Berliner Philharmonie concert hall, part of the Kulturforum on the south edge of Berlins’s famous gardens, the Tiergarten, and just west of the former Berlin Wall, is the home of the Berliner Philharmoniker, one of the world’s leading orchestras.

The orchestra’s current home was built to replace the old Philharmonie, which was destroyed by British bombers on January 30, 1944. It opened on October 15, 1963, with Herbert von Karajan conducting Beethoven’s 9th Symphony. To this day, the concert hall is highly regarded for its design and acoustic qualities. It was one of the first modern concert buildings designed with a central stage, surrounded by terraced audience seating on all four sides of the orchestral platform. Indeed, it is the model for later halls, including the Sydney Opera House, the Leipzig Gewandhaus, Walt Disney Concert Hall in Los Angeles and the Philharmonie de Paris.

How the Theft Happened

There is no available information about the theft, other than that the guestbook is missing from the Berliner Philharmoniker archives. According to an individual familiar with the archives, the guestbook had never been put on display and the archives are in a locked area not accessible to the public, leading to the conclusion that the guestbook was taken by someone familiar with, and who had access to, the archives themselves.

How to Identify This Missing Piece of History

The missing guestbook, covering a period from 1901 to 1935, had a cover created by German Impressionist painter Martin Brandenburg, who was best known for his landscapes filled with fantastical figures.

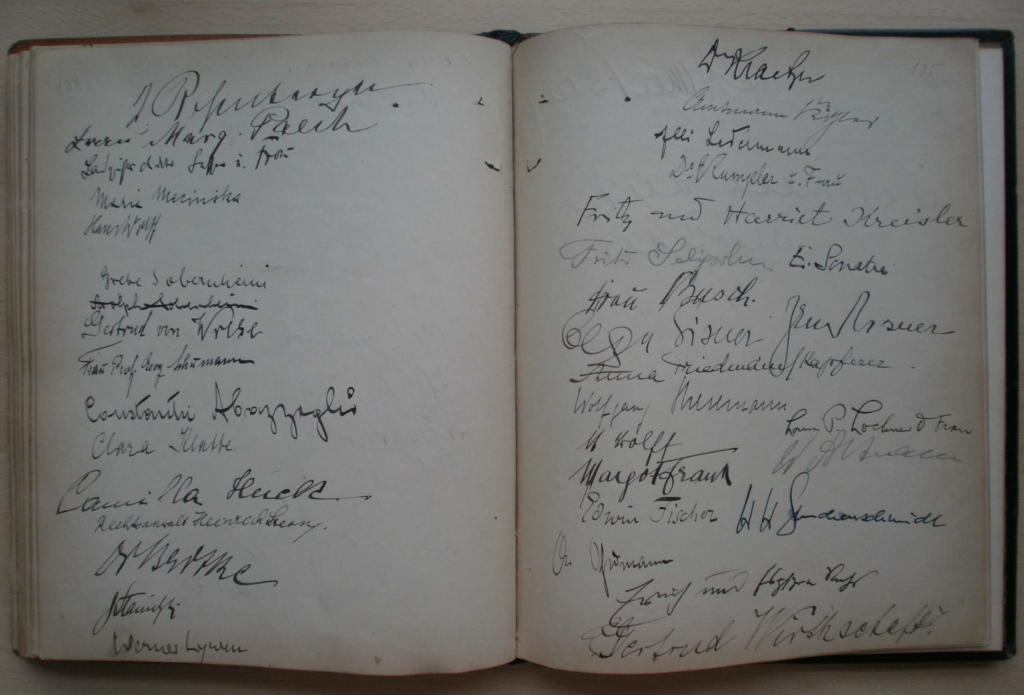

It then had 69 pages of signatures of those hosted by Hermann and Louisa Wolff for dinners and other events between February 1901 and June 1935.

The first page from February 3, 1901 shows the signature of Hungarian Arthur Nikisch, the director of the Leipzig Gewundhaus Orchestra and principal conductor for the Berlin Philharmonic Orchestra from 1895 until his death in 1922.

The last pages include the signatures of Fritz and Harriet Kreisler. Fritz Kreisler, who was Austrian-born and later an American citizen, was considered to be one of the greatest violinist of all times. He gave the premiere of Sir Edward Elgar’s Violin Concerto, a work commissioned by, and dedicated to, him.

Why This Missing Piece of History is Important

The Wolffs’ guestbook chronicles their guests for dinners and soirées at their home in Berlin, many of whom were the giants of early 20th century classical music and other cultural fields. The first page from February 3, 1901 shows the signature of Hungarian Arthur Nikisch, the director of the Leipzig Gewundhaus Orchestra and principal conductor for the Berlin Philharmonic Orchestra from 1895 until his death in 1922. Nikisch’s signature, as with those of many other guests of the Wolffs, appears on multiple occasions throughout the years of the guestbook.

Another early visitor, on February 17, 1901, was the German Romantic composer and conductor Richard Strauss. Other 20th century composers hosted by the Wolffs at their home throughout these years include Sergei Prokofiev, Igor Stravinsky, Sergei Rachmaninoff, Alexander Glazunov and Arnold Schoenberg. They also hosted Alma Mahler, the widow of composer Gustav Mahler, on several occasions.

The Wolffs’ gatherings also included renowned musicians such as:

- Italian pianist Feruccio Busoni, who later taught Kurt Weil;

- Hungarian violinist Joseph Szegiti, for whom Bartók’s Rhapsody No. 1 was written;

- Austrian-born pianist Artur Schnabel, who made the first complete set of recordings of Beethoven’s sonatas, one of 25 recordings that the Library of Congress selected to be placed in the National Recording Registry for its cultural and historical significance;

- Efraim Zimbalist, a Russian-born violinist who later became the director of the Curtis Institute of Music in Philadelphia;

- Gregor Piatagorsky, a Ukrainian cellist for whom Prokoviev, Paul Hindemith and William Walton wrote cello concertos and who later headed the Cello Department at the Curtis Institute of Music;

- Jascha Heifetz, a Lithuanian-born violinist, described by the Los Angeles Times as “the greatest violin virtuoso since Paganini”;

- Rudolf Polk, an American concert violinist who later became a Hollywood film director, film industry executive, and artistic manager for Jascha Heifetz, Vladimir Horowitz and Gregor Piatigorsky;

- Edwin Fischer, a Swiss pianist and conductor who is regarded as one of the great 20th century interpreters of J.S. Bach and Mozart; and

- Dame Myra Hess, an English pianist who, for over six years, organized almost 2,000 lunchtime concerts at London’s National Gallery during World War II, including during the Blitz.

In the related field of dance, they hosted guests such as Tamara Karsavina, a prima ballerina with the Imperial Russian Ballet and the Ballet Russe, who later assisted in the founding of the British Royal Ballet.

The Wolffs’ guest list extended well beyond the realm of music. In January 1926, Louis P. Lochner, an American journalist and author, was one of their guests. He served for many years as a foreign correspondent and head of the Berlin bureau of the Associated Press and, in 1939, he was awarded the 1939 Pulitzer Prize for correspondence for his wartime reporting from Nazi Germany. He was interned by the Nazis in December 1941 but was later released in a prisoner exchange.

What to Do if You Know Where This Missing Piece of History Is

If you recognize the cover or any pages from the Wolffs’ guestbook, have any information about this book, or know its whereabouts, please call us at 1-202-240-2355 or send us an email at contact@arguscpc.com.