Over fifty-three years ago, in June 1971, more than 30 historical firearms and other artifacts, including two engraved powder horns from 1776 and 1758, were stolen from the Old Stone Fort Museum in Schoharie, New York.

A Little History About Where the Theft Happened

The Old Stone Fort Museum is located in Schoharie County in the Mohawk Valley region of New York around the eastern Great Lakes. Schoharie County was long occupied by the Kanienkehaka, one of the five nations, along with the Oneida, Onondaga, Cayuga and Seneca, of the Iroquois Confederacy (later Six Nations with the addition of the Tuscarora in the 1720’s). Schoharie, in the Kanienkehaka language, means “floating driftwood.”

The name Mohawk Valley has its origins in the early 17th century after Dutch traders settled in the valley and established a trading post there. The Algonquins called the Kanienkehaka “Maw Unk Lin,” meaning “bear people,” which the Dutch heard as “Mohawk.” This area was a major war zone during the French and Indian War and half of the American Revolution battles in New York were fought here.

In the early 18th century, Germans from the Rhine River Valley region, who had previously settled in the Hudson Valley, came to the area and what would later become known as the village of Schoharie. The Old Stone Fort Museum was originally built in 1772 as a High Dutch (German) Reformed Church. In 1777, with the advent of hostilities in the American Revolution, the church, with the addition of blockhouses and a stockade, became a fort for the protection of the Schoharie area residents.

This stone fort was attacked by a large force of British regulars, Loyalists and Native Americans led by Sir John Johnson and Mohawk Chief Joseph Brant on October 17, 1780. At least three cannonballs struck the fort during the attack and a hole in the cornice molding left by one of those cannonballs is still visible today. That cannonball, and the original beam it struck, are on exhibit inside the museum.

Following the war, the building again served as a church until it was sold to the state in 1857 and used as an armory and militia headquarters during the Civil War. In 1889, the Schoharie County Historical Society was chartered and the stone fort became a museum, showcasing the history of the area.

Today, the Old Stone Fort Museum Complex tells the story of three centuries of rural New York history. The main museum is housed in the Old Stone Fort. The first floor displays collections and exhibits on the military, agricultural and cultural history of the region. The second floor, described as a “museum of a museum,” is straight from the Victorian Era, with thousands of artifacts, ranging from 350 million-year old fossils to a fire engine built before George Washington was born. Other buildings and exhibits in the complex include a restored New World Dutch Barn with 18th and 19th century tools, an 1890s one-room schoolhouse, and Schoharie’s first automobile, a 1903 Rambler.

How the Theft Happened

Little is known about how the theft took place, other than it occurred on June 4 or 5, 1971. Interestingly, however, four of the stolen firearms –- a 1775 musket, an 1830 musket, an 1810 Springfield rifle and a Maynard carbine -– were recovered from two brothers in the Philadelphia area in the last several years. It is very possible that these missing powder horns were sold at auction or to a private collector at some point in the last 30 years.

How to Identify These Missing Pieces of History

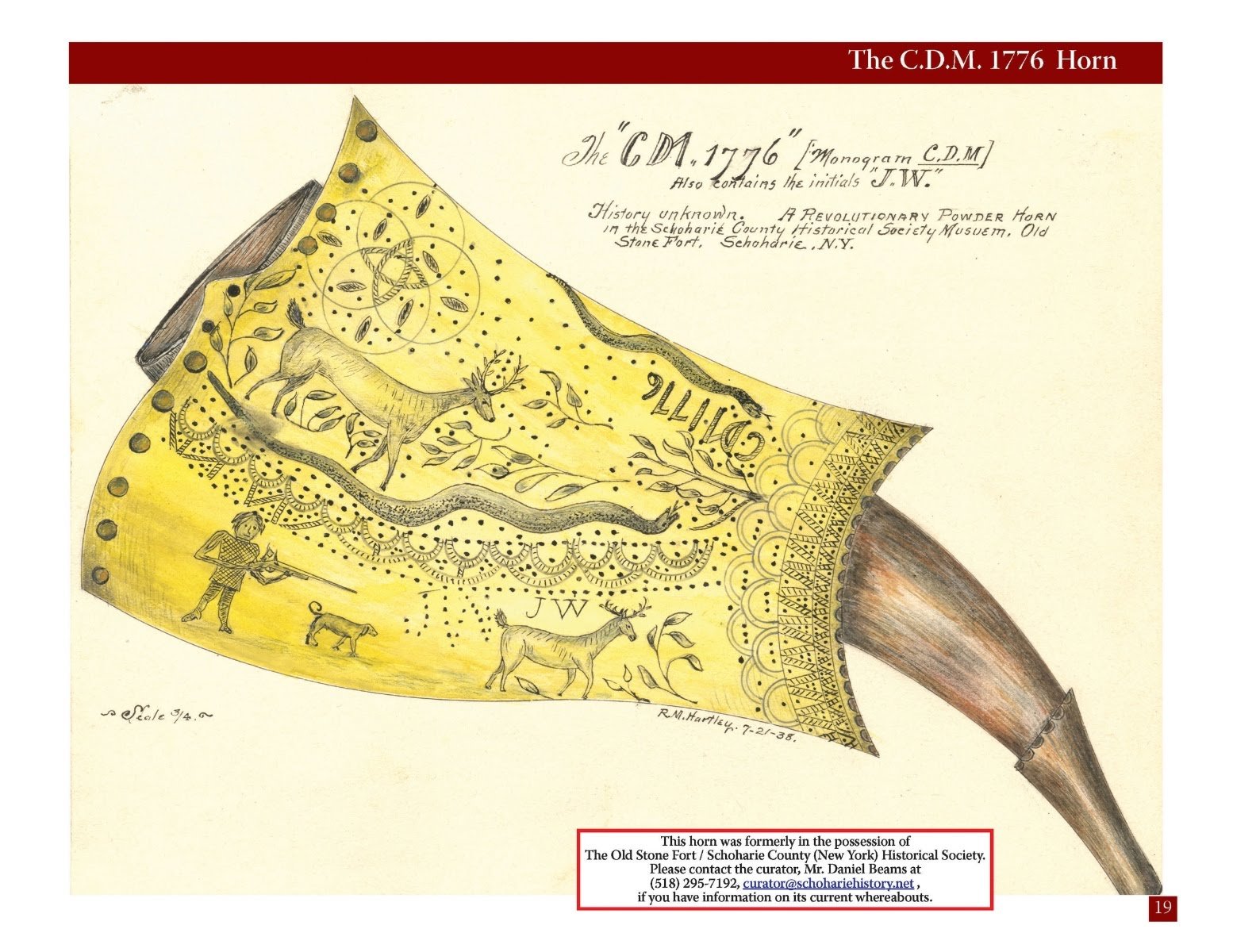

The 1776 powder horn is gold in color, approximately 13 ½ inches in length and has a flat pine butt. It features a “CDM” monogram followed by “1776” above a drawing of a stag, decorative foliage and a long snake. Below the snake is a decorative scalloped border and the drawing of a figure that has been described as a “Native American” with a long gun, a small dog and another stag. Also engraved to the left and on top of the stag are the initials “JW.” The smaller end of the powder horn also has an ornate tiered scalloped border.

The 1758 powder horn is gray in color, approximately 12 inches in length and is missing its butt. It features the owner’s name, Daniel Puegess, the location where it was made – Fort Edward, and a date of October 24, 1758. It also features drawings of animals, a man, and a crowned lion and a unicorn on either side of a large shield.

Why These Missing Pieces of History are Important

American powder horns were made from the lightweight and hollow horn of a cow or ox. They were used to carry gunpowder and were used primarily between 1754 and 1783, a period of time that included both the French & Indian War and the American Revolution.

Typically worn across the chest and secured by leather straps, a powder horn kept its owner’s gunpowder dry and easily accessible. Its curved shape was ideal for use as a funnel to transfer the gunpowder to a flintlock musket, rifle or fowler. In the American colonial world, where firearms were necessary for survival, powder horns were essential equipment.

They were also very personal accessories. Because a powder horn was hard and smooth, it was a perfect medium for carving. At its most basic level, a decorated powder horn identified itself for its owner. From this need for identification an artistic tradition emerged, with the carvings on the powder horn revealing personal, historical and geographic information about the owners and the places and times in which they were being used. A powder horn typically featured the owner’s name or initials and the date that it was carved. Often, it included details such as where it was being used, a map, a scene, or drawings of men or animals.

These objects, including the Old Stone Fort 1776 and 1758 powder horns, truly are pieces of American folk art. Author Tom Grinslade, in the title of his book on American powder horns, has given us the perfect description – they are “documents of history.”

What to Do if You Know Where These Missing Pieces of History Are

If you recognize the 1776 or the 1758 powder horn, have any information about either of them, or know their whereabouts, please call us at 1-202-240-2355 or send us an email at contact@arguscpc.com.